Size, it seems, must matter. I discovered tonight that Robert Grenier's little-seen book of poems, a poster entitled CAMBRIDGE M'ASS and covered with hundreds of little poems, each floating within its own rectangle of brightness, is larger than I thought. I had believed it was three feet by four feet (36" X 48"), but it is actually 40.5 inches wide and a remarkable 49 inches tall. Laid out on my dining room table it covers most of the available surface. And all this outrageous size for hundreds of tiny poems, some as short as a word in length.

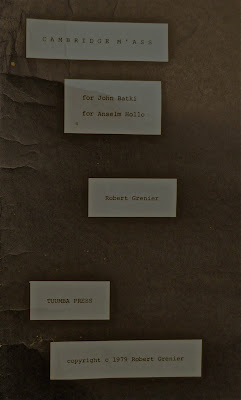

Whether this is a book or not would be a question for some, I suppose, because it is definitely not a codex. It is simply one huge page that forces the reader to move physically before it in order to read the poems. The book is, obviously, designed to be posted on a wall to make reading it easier. But even then, the ease of reading it would depend on how high the poster was hung and how tall the reader was. The evidence of its bookness appears in the colophon, which appears in the lower lefthand corner of the poster and which provides us with all the basic bibliographic information, except for the place of publication.

As I read the book I read from the left across and then down, but I read in blocks, trying desperately to read every poem and not to read the same poem multiple times. The latter proved impossible, and I'm not sure I've read every poem on the poster, but I probably did. After a while, I began to use a ruler to mark my reading.

The poems are classic Grenier: cryptic, anti-lyrical, yet sometimes lyrical, anti-poetic, but always poetic, designed to squeeze language and the thought that accompanies it into the tightest ball possible, and still allow it to move and mean and move. Grenier has a few modes of writing these poems. Some are only a word in length, but a word usually extended in length by adding a space between each letter:

A D A R O N D R O C K S

[which is obviously a reference to my own Adirondacks, which are a bit rocky in spots and which remain essentially wild even with the few thousand people that live within them]

m o r e s w e l l

[which poems between "more's well" and "more swell," maybe a reference to a day at the beach, which could be a book]

l o i k e w o i s e

[which I can read as little more than a study in pronunciation that takes us from "likewise" almost to "lakeways"]

and

i n t e r o p e r o p t a t a t i v e

[which reads like a stunt word, a word with more over-serious meaning than it can hold]

Some of Grenier's poems are but a line in length, and these tend to work most powerfully. They suggest without saying, but they don't even really show. There is usually no event being recreated, no narrative, but there is the capturing and presentation of a thought somehow connected to an event that has evaporated into forgetting.

can you get than that

[a question without the final marking of a question, and with something missing, maybe the word "more" ("can you get more than that") or maybe something entirely different, a little bit of evidence of how language falls apart when the smallest piece of it is missing, yet it persists even if fatally flawed, it means even if it doesn't have the full capacity to mean]

raining kissing deep dark outside

[a real outlier, a poem that is an event, a scene, but one presented with almost no deal, yet it remains powerful: first, because of the images we make out of these fragments, but second by the strong meter: essential a line of trochaic tetrameter (each foot an accented followed by an unaccented syllable), but the one exception to this perfected meter is the double-stressed spondee made from the words "deep dark," so that in a line of eight syllables five of them are stressed]

one o'clock shadow

[the only poem that made me laugh, as I countered this with "five o'clock shadow," though that is a shadow of an entirely different kind, not one that grows on a face, but one that grows out of the sides of trees slowly after the intensity of a noon sun]

I thought I heard a voice say Frances

[all of these unmarked poems, sans punctuation, sans reference, with a speaker but without any clear sense of who this speaker is leave us in a world almost of pure language, a world with signifiers but no signifieds, so that we have no idea who I is, we have this I report not an event but his (we assume a he) belief that there was an event, we have not a person speaking in the possible memory but a voice, something disembodied from the person, something separate, and that voice speaks of Frances, who may be someone the speaker knows or someone else entirely or no-one]

moon drawn down western horizon even as new

[a poem of almost traditionally poetic sensibilities: the moon and night, the light of the moon as compared to the horizon, the poet within the natural world, but as something separate from that world, an observer, the poem seeing it all as if if were new]

As a native Californian, this one-line poem of Grenier's (which we know is nothing but title since it's presented in all caps) reverberates with me, maybe awkwardly strongly. Anyone with a connection to a place has a personal and unique connection, and I've no idea what Grenier's connection might be to the state he moved to decades ago. HIS CALIFORNIA might be ironic, nothing good, an empty shell of a place, something unreal, unlike his own New England. MY CALIFORNIA is something of a history abandoned: a descendant of 49ers, I left the state when I was young but moved so often that California was always home, always the place where my relatives could be found. Given a choice to live anywhere, I would live in the Bay Area, where the two main strands of my family came together to make me.

But my connection to California is less important, as is my connection to my current home of Schenectady, New York, a place known more for its name than anything else. What is important here is that Grenier's poems were set down, it seems, in various places and they reflect those places. Sometimes there is snow and cold, sometimes there is sun and surf, and sometimes the names of places (the state of California, New England towns) insert themselves into the poems as if to say that language is never separate from place or object or event, that we cannot escape certain realities, even within the tight little boundaries of the iridium shine of hundreds of severely restricted minimalist poems.

A few of the poems are long, ten lines and longer, but most don't come that long, most of the longer poems restrict themselves to a view lines, and maybe a title in ALL CAPS, though usually no title at all.

THUS STREET

and so

and so and

[what does the street do but continue, and as it does you can never see the end, never finish the thought, so the poem must end with "and"]

SUNLIGHT

spread your legs like

coming from far away

species

look to like

[a remarkable poem that changes its perspective with every line, beginning with sunlight that may shine between the legs the speaker asks to be spread, suggesting opening and thus entrance, maybe of only the sun, possibly of more, but the legs are asked to be spread "like / coming from far away," as if sunlight opening new vistas, but there is that "coming" there still, that Stevensian pun stored deeply out in the open, until species appears, maybe a distant [far-away] species, maybe a pun on "specious," maybe a sense of the need to order things into categories, before ending with "look to like," possibly because looking at something can change to liking something, or maybe to move the mind back to the legs spreading "like," whatever it must be all it is is is, so we experience a language of invention before our eyes, seeing so carefully what isn't there that we might just miss what is]

M

owl

[a poem I can't quite decipher and can't quite abandon, though I wonder why the M? since "mowl" provides us with no useful word, maybe the soft sound of the wind as an m before the owl moves through it?]

POPLARS

facing water

stand as these

[the speaker sees himself at the water, facing it, with poplars around him, and he imagines himself a poplar, a tree that stands tall but moves in the slightest breeze, and he identifies himself as a northeasterner with the word "poplar," which appears in a number of poems here, because he doesn't use the western word "aspen" or the southern "popple," he uses the word "poplar" as I always done, though I am a northeastern American only by accident]

that was there there there then

that was that there that then

[there is an ultimate perfection to this meaningless meaningful poem, in its structures, in its examination of repetition, knowing that some words can be repeated multiple times in a row and carry different meaning [consider the word "that"], but that some words do not, yet the sense of a need, the sense of the possibility, of multiple meanings allows us to feel what these words might mean even if we cannot understand it]

Grenier has invented his own notation for his poetry, providing titles in all capital letters, double-spacing all the poems so that each line becomes a stanza, adding spaces between the individual letters of pwoermds. And, whether by happenstance or careful planning, he has presented his poems in a variety of versions of the book. What these formats often do is retard the speed at which his poems can be read, force the reader into a physical relationship with the page, and make the reading experience more difficult.

His Sentences (top left in the picture) is 500 cards stored in an ingeniously designed box, which makes the process of reading and then cleaning up after the reading slow. His What I Believe / Transpiration/Transpiring / Minnesota, three sequences that make up one "book" (and the last book I read last year), consists of reproductions of his scrawled handwriting, as he began the process of developing his austere four-word four-color poems. In this book (the middle one above), just interpreting the surface of the text takes time. In his Sentences Towards Birds (bottom right) the reader is presented with cards in an envelope, a small taste of the more arduous (though pleasant) experience to follow in the full Sentences. And in CAMBRIDGE M'ASS, readers must move their entire bodies to read the book. This book is so large and its poems so small and numerous that a picture of the entire poster hides all the poems, reducing all of them to white rectangles on a field of black.

The message here is clear: "You are reading too fast. Slow down. Take your time. Allow the words to seep into your mind. Find a way to see these poems. Try to understand how these poems escape understanding, and how they do not. Embrace the cryptic quality of the poems. Embrace the physical rigors of reading these poems.

Enjoy yourself.

Or at least enjoy reading the poems.

_____

Grenier, Robert. CAMBRIDGE M'ASS. Tuumba Press: np, 1979.

ecr. l'inf.

View comments